I have… estimated that about 300 different experiments were made in which chocolate was the basic ingredient and in which soy flour cooked and raw, rice flour, potato flour, potato starch, reground tapioca, wheat flour, oatmeal and oat flour, were the principle cereals used. Coffee in soluble form and pulverised roasted coffee were also tried and caffein extracted from coffee was used. Flavoring agents included peppermint, vanilla, lemon and diacetyl. At one time, a small amount of kerosine was used to throw the product off-flavor. Different levels of whole and skimmed milk powder and both corn and cane sugar were used.

These are the words of Colonel Paul P. Logan. While serving as head of the Subsistence School from 1934 to 1936 Logan (then still a Captain) started working on an emergency ration. This would result in a fortified chocolate bar that was then popularly known as the Logan Bar. This name was still used after official adoption during the war by the U.S. Navy.

Captain Logans work was initiated as a result of new directives for an emergency ration that was issued in 1935. This new ration should have the highest amount of calories in a smallest possible package, usable under any climatic conditions, and should be palatable enough for continued use.

The new U.S. Army Emergency Ration presented in an article of the Life magazine. Note that the ingredients are not listed on the label. The bar is dated June 1937 and indicates that this is from an experimental procurement for testing prior to acceptance.

As to how palatable this ration should be, there was the idea that it shouldn’t taste better than a boiled potato in order that the ration wasn’t consumed as a candy upon being issued, but kept in a pocket or pack for when the emergency arose. (The use of the small amount of kerosine was just for that purpose and was only tried once, but for some reason in any popular description of the D Ration this is still sensationally mentioned as is being part of the ingredients.)

The term emergency ration was officially droped after WWI and since a ration was considered all the food needed for one man for one day, there was considerable discussion about under what name to adopt the new chocolate bar. Finally the matter was settled when a new kind of classification was adopted. Fresh or preserved food prepared in the field similar to the garrison ration were considered Field Ration A and B respectively. A new canned field ration, that could be carried by the individual soldier, under development would be adopted as Field Ration C and that leaves the the chocolate bar to become the Field Ration D.

Individual bars of the D Ration are referred to as D-bars.

The Logan bar was first adopted as the Emergency Ration on November 9, 1938. On 17 October 1939 this emergency ration was officially standardised as the U.S. Army Field Ration D.

One complete D ration as published by the Life magazine.

There is some confusion as to what exactly a ration is. The chocolate bar was intended to replace only one missed meal, so three bars make up one complate ration of three daily meals. Since the D Rations were usually packed as a single bar and were individually labeled as a D Ration they are erroneously considered as one complete ration. When looking at production numbers it should be kept in mind that these numbers are actual complete rations of three bars.

Early production run from October 1941 till November 1942 and almost reached 40.75 million rations. That is over 122 million bars. Additional large orders were placed early 1943 raising the total even more!

These additional orders were not only for the U.S. Army, but also for other government agencies like the Food Distribution Administration and the Federal Surplus Commodities Corporation as well as probably the U.S. Navy and the Army Air Force.

Planning for D-day called for every soldier making the assault would carry one K Ration and one D Ration. This means that every soldier was issued one of K Ration’s Breakfast, Dinner and Supper units each and three D-bars.

Follow up troops are being issued their field rations before going over to France three days after D-day. Note the opened master cartons for twelve D-bars in the lower left corner. The soldier bending over is just opening another case of D-bars.

The price for one D Ration was, as calculated in January 1943, to be 15.7 cents. That's is just about 5 1/4 cents per D-bar.

An individual 4-ounce bar contained 600 calories, so a complete D Ration of three bars contained 1800 calories. This was less then half of the calculated 4000-4500 calories needed by a soldier, but it kept a man going when nothing else was available.

An original D-bar stating 448 calories instead of the official 600. Interestingly it is produced in July 1944, but still uses the old style of label.

(This is from my own collection and is imprinted with the old letter-press printing technique that you can't fake with modern techniques. Beware of other Cook Chocolate Co. cartons out there, they might be fakes!)

Formula

Basically the D-bar was a 4-ounce chocolate bar with raw oat flour added. Due to the high percentage of chocolate solids the melting point of the chocolate was raised from 92ºF (33ºC) to 120ºF (49ºC) so it would be usable in the tropics. The high percentage of the choclate solids, however, also makes it more bitter. At the time of development this was seen as something positive since it prevented the men from using the chocolate bar as a candy.

The addition of oat flour increased the protein content and because the flour absorbed most of the cocoa fat it made the bar less susceptible to rancidity. The reason to use oat flour over other cereals is because oat flour is over 90% assimilated in digestion, therefor more nutritious.

The production of the chocolate differs from commercial process. The chocolate liquor is lightly mixed into a rough paste with the sugar and oat flour. Instead of running this mix through malingers, congers, rollers and other refining machines as is done in the commercial process, the mix is kept rough. The chocolate made from this rough mix will not run and therefor cannot be poured, not even when heated and is forced with great pressure into the moulds.

This process results in a higher melting point of the chocolate and will therefor not melt in hot climates.

Although raising the melting point made the bar useful in warmer climates, it also made the bar hard to bite through. In fact, the chocolate became harder upon aging. By the time a ration reached the frontline soldier it might be already a year old and the chocolate had became hard as a rock.

The formula for this concoction remained unchanged through out the war:

Thiamin Hydrochloride is a synthetic B1 vitamin. Although the ration is to replace just a missed meal or so, it was considered feasible to fortify the ration with any vitamin possible. It was found that only the B1 vitamin would not deteriorate or affect the flavor of the chocolate. (The B1 amount is sometimes labeled as 150 I.U. on the 4 oz. bar.)

4-ounce bar

The size of the 4-ounce bar is given as 3 13/16" long, 2 1/8" wide and 3/4" high (approx. 97 x 54 x 19 mm). The bar had 1/8" deep grooves in its top surface, dividing the bar in six equal parts. The sides having a slight slope and the ends being rounded at the top.

The 4-ounce bar in its cellophane bag. Being over 75 years old the cellophane became brittle and cracked along the seams. (Photo: 1944Supply)

2-ounce bar

A 2-ounce bar was also developed for use with other rations. It was made with the same formula, but with different dimensions. The early 2-ounce bar was basically a 4-ounce bar cut lengthwise in half.

The early longer type of the 2-ounce D-bar as included in the K Ration.

The length of a 2-ounce bar compared to a 4-ounce D-bar packaging.

This 2-ounce version of the D-bar proved too long to fit conveniently in the K ration box without tearing the cellophane bag. In 1943 the size was standardized as 3 1/8" long, 1 9/32" wide and 13/16" high (approx. 80 x 33 x 20 mm). This bar was divided by two 1/8” deep grooves across.

The later shorter 2-ounce D-bar. (Photo: 1944Supply)

Even an 1-ounce bar was produced in half the height of the 2-ounce bar for use as a candy component in other rations. This bar had three serrations.

Packaging

Now that a palatable emergency ration was developed, the next problem was how to package it. Early directions instructed an aluminum foil wrapping with an overwrapping of parchment paper and a kraft paper label band running around the bar lengthwise.

The new experimental D Ration broken in half and showing the early aluminum foil with paper wrapping. The bar appear to be a rectangular block without the grooves or rounded ends, indicating experimental production. Note the course texture of the chocolate.

Interestingly, the kraft paper band was placed in such a way that the label is positioned at the underside of the D-bar

Early production D-bar wrapped in parchment paper with a kraft paper band. From the damaged corner we can see that there is no aluminum wrapping underneath.

Note that the band is placed with the label at the underside of the bar.

With the war looming, aluminum foil became a critical material. The packaging with only just the parchment paper wasn’t found satisfactory, so another type of packaging needed to be found to pack the D Ration in.

The best and practical solution was, as specified in February 1942, to package a single bar in a cellophane bag that was inserted in a cardboard box that was coated with a synthetic wax like the K Ration’s inner carton. No critical material was used, yet offered adequate protection against moister and (poison) gas contamination, and that was light to carry and easy to open.

Shown here is a D-bar that has been attacked by vermin. Although the carton only show a few holes, the bar is tunnelled throughout. Even the cellophane is half eaten.

As an alternative packaging, three bars were indivually sealed in a cellophane bag and then the three bars were packed together in one carton. The middle bar was placed upside-down so that the bevelled sides would fit snugly together. The carton was also coated with synthetic wax to render it water and insect proof. It appears that this package was mainly used by the USAAF.

A 3-bar carton of the D Ration.

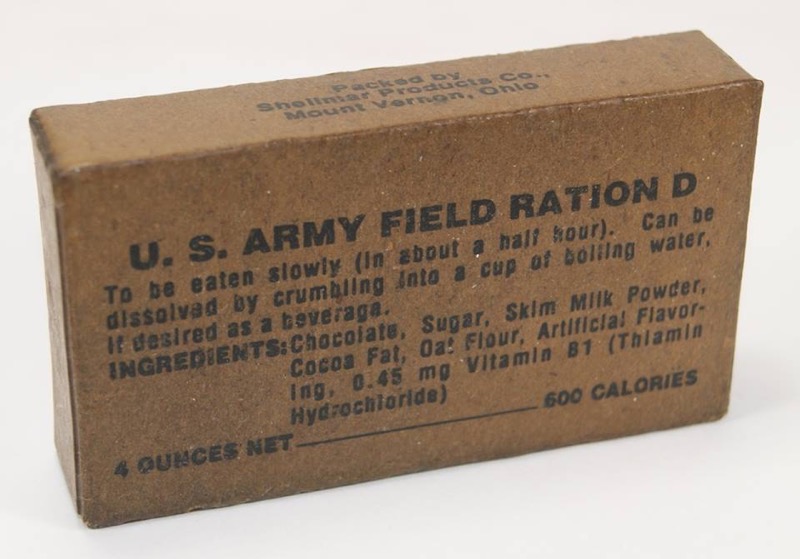

Only one panel of these cartons were printed with the instructions and ingredients. The instructions warned that the bar should be eaten slowly because it was found that when eaten too fast it could cause stomach ache or heart burn. It also suggested that the bar could be crumbled into boiling water to make a hot cocoa drink.

Furthermore it stated on the same panel the company who packaged or produced the bar.

Early label of the D Ration packed by the Shellmar Products Co. for the Peter Callier Kohler Swiss Chocolate Co. The label is repeated on the back panel as well, which is unusual. (Photo: 1944Supply)

Complaints from the battle front were received that the bars were sometimes being thrown away because the chocolate had whitened (called blooming) on the surface.

In April 1943 it was directed that the folowing instruction was to be included on the front panel of the packaging (both 2- and 4-ounce bars): "Storage conditions may cause the surface of the bar to whiten. This does not affect its eating quality."

Later style label with the new Ration, Type D nomenclature. Note the added warning against blooming. The malaria warning is on the back panel.

In February 1944 a directive was issued that the back panel should read a warning against malaria:

"NOTICE: Mosquito bites cause malaria.

If you are in a malaria zone, keep your shirt on and your sleeves rolled down. Use mosquito repellent out of doors between sunset and sunrise."

The back panel of a D-bar packaged by the Cracker Jack Co. showing the malaria warning.

In May or June (no definitive date found yet) 1943 the U.S. Army changed all ration nomenclatures from "U.S. Army Field Ration …" to the "Ration, Type …" So the D-bar became officially the Ration, Type D.

Enlargment from an official publication about the confections used in the rations, 1945.

With the change of the nomenclature the design of the printing on the panels changed as well. The front panel carried the name of the ration plus instructions for use, the back panel had the malaria warning on it and on one of the side panels were listed the ingredients while the other side panel showed the packagers or manufacturers name.

It appears that some 1944 production still used the older style of labeling.

It is confusing that both packaged by and manufactured by is used. The name on the carton is the company that is awarded the contract for delivering the D-rations.

When a packaging company was awarded a contract for the ration, they sub-contracted the manufacture of the chocolate bars to other companies. This makes sence since that the packaging was a specific proces of heat-sealing cellophane bags, inserting in a carton, glue these shut, and then immerse the cartons in hot wax. All on an automatic production line.

If a chocolate manufacturer got the contract then their name is placed on the carton, even if the packaging was done by a sub-contractor. Sometimes the manufacturer is also the packager, depending on its capabilities.

This is what the official specifications stipulates: "The name and address of the contractor shall be placed on one side panel […]", "If the manufacturer of the chocolate bar and the packer are not the same, the name of both companies may appear here at the option of the packager." (italics by me).

Known contractors of the 4-ounce bar are:

Hershey Chocolate Corp.

Wm. Wrigley Jr. Co.

Cracker Jack Co.

Cuneo Press Inc.

Shellmar Products Co.

Charles A. Brewer & Sons

Blommer Chocolate Co.

Bag-O-Matic Packaging Div.

Walter Baker & Company Inc.

Cook Chocolate Co.

Peter Callier Kohler Swiss Chocolate Co.

McKay-Davis Co.

R. B. Davis Co.

Moler Swiss Chocolate Co.

Two D-bars made by Hershey showing front and back. One side panel labels Hershey as manufacturer (left) while the other side panel lists the ingredients (right).

As mention earlier, at the end of 1942 the Army had procured some 122 million D-bars with additional production in early 1943. Offensive operations were just started in the fall of 1942 in the Pacific and North Africa, so there were plenty of D-bars to support these and future operations for the next year.

There are exeptions to that statement of course. See the paragraph about USMC procurement below.

In June 1943 studies were started to see if the packaging of the D-bar could be improved. This study also included the 2-ounce bar packagings. Although the waxed carton was found satisfactory for the time, the single-ply cellophane bag was found inadequate. In February 1944 specification called for a 2-ply cellophane bag to be used. This bag, however, proved too stiff to be used with heat-sealing machines and as of May 1944 a newly developed single-ply cellophane bag was chosen.

Since there were enough D-bars at hand to last throughout 1943, production resumed early 1944. The new packagings should now read Ration, Type D and includes the warnings about the “blooming" and malaria. According to one source 52 million additional D Rations were produced in 1944 and 1945. That’s another 156 million D-bars! There was quite a surplus of D Rations when the war ended.

Master cartons

It was found feasable to pack twelve bars together and the earliest way this was done was by placing twelve bars on top of each other and overwrap these with sturdy kraft paper. The kraft paper wrapper was printed with a label showing the nomenclature, number of bars (cakes) and the manufacturer. So far this type of packaging has only being observed produced by Hershey. (Probably because they were the only manufacturers at this time.)

A master packaging of twelve D-bars. Since the packaging is dated before the introduction of the waxed cartons it is very probable that there are 12 paper wrapped D-bars stacked on top of each other and then overwrapped with kraftpaper.

When the individual bars were packed in a wax coated carton the master packaging changed to a cardboard box holding twelve D-bars.

Left: a master carton for one dozen single D-bars made by Hershey. Although the date is May 1944, the nomenclature is still “U.S. Army Field Ration D”.

Alternatively, eight cartons with three D-bars were placed in a master carton, totaling 24 bars. Six of these boxes were placed in a wooden crate for shipment. Both crates containing a total of 144 individual bars.

A master carton for 8 packagings containing three D-bars each. Note the kraft paper tape running around the carton, sealing both top and bottom flaps.

The individual cartons were sometimes referred to as inner cartons and the master carton as the outer carton.

Two methods were allowed for closing master cartons. One method was that the flaps of the front and back panels (both top and bottom) would overlap one inch when closed and sealed with a waterproof glue. The other method was that the flaps would meet without any noticable gap and a waterproof kraft paper tape was placed running completely around the carton covering the seam where (both top and bottom) flaps would meet.

Wooden shipping case

12 such master cartons were placed in a wooden case of construction simular to the K Ration case. A case contained a total of 144 individual bars.

Just like the K Ration cases the labels are stencilled or printed on one of the end panels.

Early cases mentions that the bars are packed per 12 in a carton, but do not say that the bars are packed individually in a carton too. Included are the date, contract number and the contractors name and address.

A case has been opened and shows how two tiers of six master cartons fit in the wooden case. A master carton is opened as well showing how the individual D-bar cartons are packed.

Note how the outer flaps are closed with an inch overlap.

(photo is taken from the book "Food in the American Military")

A wooden case for 144 bars packaged per dozen in cartons for the U.S.M.C.

Later the information stencilled on the cases only refer to the individually packed cartons. The single bars are still overpacked in a master carton, though, as per specifications.

The contractor, contractors address, contract number and date of packing is stencilled on one of the side panels.

Obviously, there are small deviations observed in the label designs from the above shown specifications.

The crudely stencilled end panel of a later produced case complying with the new nomenclature: Ration Type D.

It is interesting that it mentions that the bars are packed individually in a carton, but not that 12 bars are still overpacked in a master carton. (Photo courtesy J. Willaert)

2/3rd of a front panel of a D Ration wooden case (I artistically completed the missing top part so you can get an idea what it should look like.)

Note how the two parts are connected with corrugated staples as accepted per specifications if the ends are of multiple construction.

In 1944 the tin shortage became less critical and in the fall of 1944 it was decided that twelve single bars (4 rations) were to be packed in a rectangular can for overseas shipment. Twelve cans were packed in a wooden crate. The single bars only needed to be cellophane packed when placed in a can, but the cellophane then was to be printed with the same information as printed on the cartons previously used. (If the bars were still being packed in cartons the cellophane remained blank)

Right an illustration from the Quartermaster 17-3 manual “Rations and supplements”.

Top labeling of the canned D-bar with the ingredients and malaria warning (above). The nomenclature and instructions are printed on the underside of the bar (below).

Note that the D-bar is packaged by the McKay-Davis company.

USAAF

As mentioned above, an alternative packaging consisted of three bars packed together in one carton. These cartons were mainly used by the USAAF and were included in the B2 Jungle Emergency Parachute back pad.

Shown here is an early USAAF bailout kit with the 3-bar D Ration inserted.

Next to the D Ration is an U.S. Army Air Corps Ration that contains two 2-oz. D-bars, a bouillon envelope, two 2-oz. packages of the malted milk and lemon flavored dextrose tablets, and two sticks of chewing gum.

The contents of the USAAC Ration are shown in an official Signal Corps photo below.

Although the specification for packaging three D-bars together was still issued in late 1944, I have not seen such a packaging yet. It should read "Ration, Type D” and should carry the warnings against blooming and malaria as well.

As an alternative the D-bar was wrapped in greaseproof paper to be included in emergency kits with other components like the Army Air Force’s E-3 Emergency Sustenance kit. (photo left)

A D-bar wrapped in grease proof paper showing yet another nomenclature. The paper wrapped bars are probably specific Navy or other government agencies procurements. (Photo 1944Supply)

USMC

The Marine Corps also showed interest in this new emergency ration and these D-bars for the Marine Corps were packed in cartons labeled: U.S. Marine Corps Field Ration D or U.S.M.C. Field Ration D.

It would be very interesting to find a Master carton specifically made for a Marine Corps order.

These were procured directly by the Marine Corps from Hershey and used the same style of labeling as the Army. Later all field rations were procured through the General Quartermaster of the U.S. Army for the Marine Corps. So, no special Ration, Type D packagings for the Marine Corps were made.

Early production of the D-bar by Wm. Wrigley Jr. Co. for the Marine Corps.

The end of an USMC D Ration case is shown here. The fact that D Ration cases are hard to find anyway, makes this one is even more rare!

Note that the contract number has a “M” prefix which indicates that this contract was awarded directly by the Marine Corps (through the US Navy). This would also explain the contract date: November 1943. Appearantly the US Army Quartermaster was unable, or unwilling, to supply D Rations, forcing the Marine Corps to order the rations themself from Hershey.

Men of the 1st Marine Division are coming of the line in Cape Gloucester. Upon boarding the truck they were handed a D-bar. You can see several marines nibbling on the chocolate bars.

These bars might be D Rations made specially for the Marine Corps, or are the standard U.S. Army D Rations. They even might be D-bars made in Australia!

Navy

The U.S. Navy was also very interested in the new emergency ration. Although the Navy would never accept anything that has U.S. Army written on it, the new D-bar would be useful as a component in its life raft survival kits. The Navy procured the 2-ounce version for its own use labeled "Logan Emergency Bar (conforms to specification for Army Field Ration “D”)".

Right is illustrated a life raft ration that includes four 2-ounce D-bars. Note that one bar is of the shorter variety.

Navy’s own 2-ounce D-bar. This is the same 2-ounce D-bar that Rockwood manufactured for the Army, but with a different wrapper. Who is fooling who here.

(Photo: 1944Supply)

The 4-ounce bar was also used in some life raft rations. This version still used the early packaging method of being wrapped in parchment paper with a band of kraft paper reading “U. S. NAVY, AIRCRAFT AND LIFE RAFT EMERGENCY RATION SWEET CHOCOLATE” dated May 1943.

British-made

As part of the lend-lease agreement the D Ration was also manufactured in Britain by Britsh manufacturers. It is not known in what numbers and when these were produced.

The British-made D-bars were conform U.S. Army specifications, although slight differences in dimensions have been observed.

Apparently, the D Ration was also manufactured in Australia for troops in the Pacific theatre, but further information has not been found yet.

A British-made D-bar packaged by Rowntree Co. Rowntree was a well known chocolate manufacturer in England and made the famous Kit Kat snack.

D Rations made by Cadbury.

It is interesting to note that the British Emergency ration was packed in a metal container, an item being critical material needed for the war effort.

With the experience gained in packaging the U.S. D Ration in a wax coated cardboard box it would make sense that this type of packaging could also be used for packaging the British Emergency chocolate bar.

Shown here is the British 8 oz. Emergency ration next to a British-made 4 oz. D Ration.

The embossing of the tin carry a warning that the ration should only be opened on authority of an officer.

Maybe the British industry didn’t had enough capacity to produce the protective cardboard packagings to satisfy the needs demanded for the Emergency ration, as there was already a strong demand for the cardboard 24 Hour Ration. Or the carboard packaging wasn’t deemed strong enough for this type of ration that was to be carried in a pocket or pack for a prolonged time until the emergency rose.

Top left: US made D Ration in waxed cardboard. Top right: US made D-bar in cellophane. Bottom left: British Emergency ration. Bottom right: British-made D Ration.